by Lizzy Baus

Quick Summary

In a June 6 Association for Library Collections & Technical Services (ALCTS) preconference, presenters from East Carolina University and Columbia University described their efforts and projects to create more community-based and inclusive digital collections.

On June 6-7, 2017, the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services (ALCTS) virtual preconference entitled “Diverse, Inclusive and Equitable Metadata” was held. The first session of this two-part preconference, “Outreach and Inclusivity in Digital Libraries and Institutional Repositories,” consisted of two presentations and lasted one hour.

The first presentation was “Digital Project as Community Outreach: A New Way of Approaching Metadata” by Patricia Dragon, Allison Miller Simonds, and Amanda Vinogradov. In Greenville, North Carolina, there is a part of the city that once contained a thriving African-American community centered around the Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church. In the 1960s, the city razed and redeveloped the area into a grand park area. However, this action and the treatment of the community left many of the former residents feeling ignored at best. As a small step towards addressing this gap, East Carolina University partnered with the Sycamore Hill Missionary Baptist Church and representatives of the city of Greenville to host a community scanning event they called Beyond Bricks and Mortar.

From the very beginning the community was involved in this effort. The university librarians made a point to involve community members in the planning process. The event itself was held in the fellowship hall of the (now relocated) Sycamore Hill Church, and members of the community were invited to bring items about the Shore Drive community via postcards sent to their homes. Once the community members arrived, they were greeted by staff and ushered through a four step process.

The first stop was a welcome table. At this location attendees were assigned a number to help track them and their items through the process. They were each provided an inventory form to list the items they’d brought to be captured.

The second step dealt with the collections and cataloging aspect. Here a team of two staff spoke with each patron about their items and recorded the information on metadata forms. The conversations focused on the description of the items and the patrons’ point of view – who are the people featured? What memories are associated with that house? – and so on. Each patron was assigned a plastic bin to contain and organize their items. This table also gave the participants information about digital collections, a release form describing the situation, and tips on caring for items in their own homes.

Once the metadata forms were completed, participants could spend time in a comfortable waiting area stocked with food and drinks and in full sight of the whole room.

The final step of the event was to do the actual scanning of the items patrons had brought in. Library staff operated three scanners in plain sight of the patrons – the organizers felt it was important to make sure the patrons could watch the whole process and follow their own items. The scanning team organized materials by scanning needs rather than by patron, though of course everything was tracked and coded properly. In addition to the items brought in, the scan team scanned the metadata forms for each item in order to preserve the information. The digital images were all returned to the patrons on flash drives.

The event attracted six patrons who brought in a total of 34 items. For a future event, the organizers would change a few things. They reflected that patrons might appreciate a broader window of time and the opportunity to make an appointment to have their items scanned. Another idea was to have a series of events centered on the Shore Drive community rather than one isolated event. Most importantly, a similar future event should have a new name – something that speaks to the community more than “Beyond Bricks and Mortar” might.

After describing the Beyond Bricks and Mortar event, the presenters went on to discuss some of the issues they faced in dealing with the materials they encountered. The major difference between the fruits of the scanning day and, for instance, a newspaper photo collection, was the context. Because the event, the conversations, and the metadata forms focused so strongly on rich descriptions and community point of view, much more information could be shared, such as the names of people and places, relationships, memories, and so on. In cataloging these items, the librarians faced some difficult questions about what is really important in these items. Should they explicitly call out the race of the people in the photos? They decided that, like much of this project, the answer was contextual. There were also several questions about vocabulary representing differing thoughts on the same topic. For instance, the city of Greenville had referred to the homes in the Shore Drive area as “substandard,” but the people of the community regarded them as a point of ownership and pride. This example and others highlighted the fact that vocabulary matters and can be used to reflect historical injustice. The librarians involved decided to err on the side of including more detail rather than less, and they tried as hard as possible to use the patrons’ own language to describe their community.

In all their digital collections, East Carolina University attempts to involve and respond to the community as much as possible. There is a very strong focus on cooperation and communication within the library and in the community.

The second presentation was “Doing Justice to the Humanities: Increasing Inclusivity with More Specific Subject Description,” by Brian Luna Lucero. The Academic Commons repository at Columbia University is in the process of moving to a new management tool, and this provides the perfect opportunity to examine past practice and transition from one subject heading system to another. Academic Commons contains about 22,000 items covering all sorts of departments and information. Previous practice was to use ProQuest Dissertation Subjects for each item. This vocabulary consists of 411 terms, 189 in Behavioral, Natural, and Physical Sciences and 222 in Arts, Business, Education, Humanities, and Social Science. This is not nearly enough to describe the topics of scholarly work in anything more granular than very broad strokes. For instance, the whole field of Law is covered by just five terms, which makes it vastly underrepresented and too broad to be useful to scholars of a particular type of law.

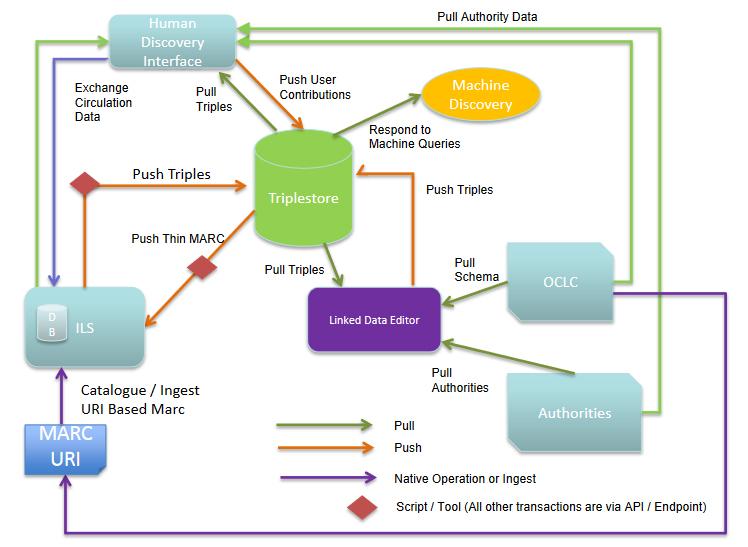

The solution to this problem of scale is to use the Faceted Application of Subject Terminology (FAST) vocabulary derived from the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). This offers about 1,800,000 terms, including geographic locations, names, titles, topics, and more. Since academic work in the humanities often focuses on one name or title, this offers much more specific access to materials. It is certainly more granular than labeling items “Art” or “Music.” Since FAST is based on LCSH as well as linked data, each term has its own uniform resource identifier (URI) with references from language variations, other forms of the term, and other terms.

The use of this vocabulary offers some distinct advantages in terms of inclusivity and interconnection. Because the terms are more granular, subject searches are more useful to researchers looking for something specific. The more specific subject terms also allow the bulk of the item description to be leaner; findability of particular topics no longer depends on indexing abstracts. Relatedly, this also offers the topics greater visibility; it also makes the data easier to crosswalk to other systems. In addition to specificity, FAST allows researchers to combine and “stack” topics, carving out a particular niche that would not have been possible with the too-broad terms of ProQuest.

There are also some challenges and disadvantages associated with transitioning to the FAST vocabulary. Chief among them is the challenge to train catalogers – in this case, usually undergraduate students. ProQuest, with only about 400 terms, is small enough for one person to know well. FAST, with almost 2 million, is far too vast to know intimately. Accordingly, the library now puts more emphasis on finding and understanding “aboutness” in its cataloger training. The greater quantity of terms also means that there is increased time per item for subject assignment as catalogers look up terms on the fly. One solution proposed was the idea of local cache of subjects frequently used. It would be preferable, though, to use a URI-based system, which would be controlled and linkable.

Another major obstacle is the retrospective enrichment of items cataloged using ProQuest. There are currently about 15,000 records that need FAST subject assignment. Some of this can be accomplished using natural language processors and programs like Named Entity Recognition of Geographics. Though this speeds up the process, human cataloger eyes are still needed. For instance, the automated system cannot immediately tell if a text is referring to Manhattan, New York; Manhattan, Kansas; or Manhattan, California.

The project continues to improve and progress, and the presenter plans to release some of their documentation in the near future.

See the official report of this preconference on the ALCTS News website.