Quick Summary

Access to affordable high-speed broadband, devices, and digital literacy training are essential to Native nation rebuilding. Tribal libraries—with public computers, free Internet access, and patient staff—are well positioned to foster digital inclusion.

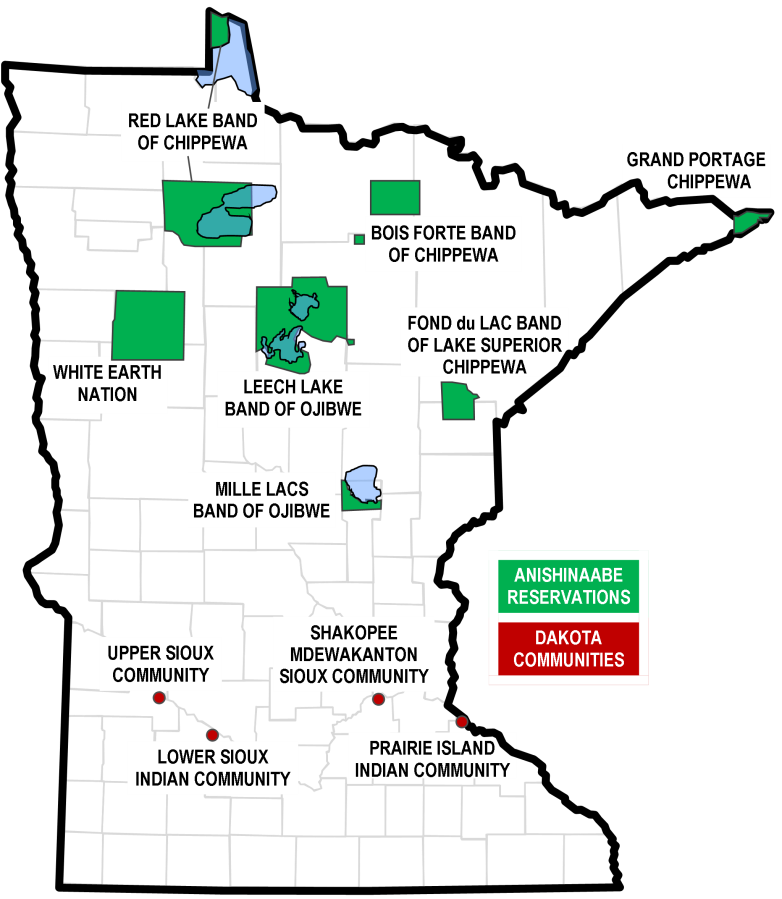

Minnesota’s eleven tribal nations are sovereign nations and have the right to self-govern. Self-governance includes but is not limited to managing tribal lands and natural resources, defining tribal membership, regulating tribally owned businesses, administering tribal law enforcement, and engaging in government-to-government relationships at the federal level.

Information access, exchange, and preservation strengthen all of these areas; as more information is stored, organized, and communicated digitally, access to affordable high-speed broadband, devices, and digital literacy training also become interwoven necessities for Native nation rebuilding. Tribal libraries—with public computers, free Internet access, and patient staff—are well positioned to foster these connections in support of sovereignty.

Digital inclusion, which the National Digital Inclusion Alliance defines as “the activities necessary to ensure that all individuals and communities ... have access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies,” is a complex, evolving process aiming to “reduce and eliminate historical, institutional, and structural barriers” so “all individuals and communities have the information technology capacity needed for full participation” in society.

But in tribal libraries, this concept of “inclusion” can be deceptive: Simply including tribes within existing non-tribal frameworks undermines sovereignty. Instead, digital inclusion efforts in tribal communities must start from the ground and build their way up. The digital-inclusion-services tribal libraries implement are rooted in each tribe’s specific needs, strengths, environments, histories, sociopolitical contexts, economic development plans, and future goals.

When developing digital inclusion services, however, tribal libraries face added challenges of basic connectivity: Broadband availability in Minnesota’s tribal communities lags behind that of the rest of the state. According to a 2016 federal report, “Tribal Broadband: Status of Deployment and Federal Funding Programs,” 33 percent of people living on tribal lands in Minnesota are, by state definition, “unserved,” compared to 12 percent of all Minnesota households as detailed in the 2016 FCC Broadband Progress Report.

The Association of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums (ATALM) documents similar disparities in its 2014 report, “Digital Inclusion in Native Communities: The Role of Tribal Libraries.” ATALM’s report states that only 89 percent of tribal libraries surveyed were able to offer Internet access to their communities. Likewise, while virtually 100 percent of rural public libraries reportedly provide public computers, only 86 percent of tribal libraries do. And while 87 percent of rural public libraries provide technology training, only 42 percent of tribal libraries have the capacity to do so.

Funding is central to this conversation. In Minnesota, tribal libraries can leverage basic resources from Minitex, but often depend wholly on federal grants to sustain and develop their own services. Funding levels may fluctuate drastically from year to year, particularly during federal upheaval. At the same time, even when funding is available, small libraries with three or fewer staff can become overwhelmed when grant administration is added an already demanding workload.

Implementing digital inclusion services can be difficult, but sustaining and expanding these services is even more challenging. And yet this is what tribal libraries do: Confront seemingly impossible challenges in order to strengthen tribal sovereignty and uphold cultural expression.